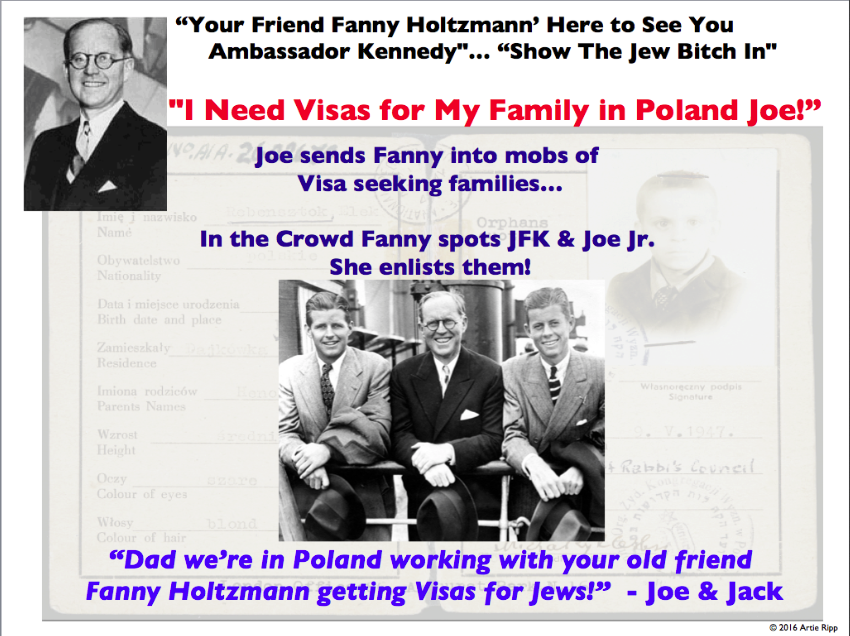

Because the British held her in high esteem, she was able to obtain British visas for hundreds of European Jews seeking to escape the Nazis; she was aided in this work by Joe and Jack Kennedy, then in their early twenties, the sons of the anti- Semitic United States Ambassador to Britain, Joseph P. Kennedy.

Holtzmann also used her contacts, including Justice Felix Frankfurter, to try to persuade President Roosevelt that extraordinary efforts were required to rescue Jews from the Nazis; Fanny's idea was for the United States to settle half a million refugees in a sparsely populated area either in southern California or the Nevada desert.

Discouraged by Roosevelt's lack of commitment to rescuing Jews after a personal meeting, she gathered support from leading Republicans.

The scheme, which she incorporated as the Association for the Resettlement of Oppressed Peoples, eventually came to naught, but Holtzmann continued her mission of helping refugees and families on an individual basis. She also played a leading role in bringing dozens of children from an Actors' Orphanage in Britain to the United States, and worked with Jewish leaders in an unsuccessful campaign (in which Justine Wise Polier also participated) to secure the passage of the Wagner-Rogers bill to admit 10,000 refugee children to the United States.

Morris “Two-Gun” Cohen was the one and only Jewish Chinese General and, for a time, was head of the Chinese Secret Service! The official languages (in order of importance) in the Chinese Secret Service, were Chinese, Yiddish and English.

Morris “Two-Gun” Cohen was the one and only Jewish Chinese General and, for a time, was head of the Chinese Secret Service! The official languages (in order of importance) in the Chinese Secret Service, were Chinese, Yiddish and English.

CALGARY, Alberta, Canada — What is a nice Jewish boy from Western Canada doing as a General in the Chinese Army? Well, not exactly a boy, maybe not so nice, but definitely Jewish.

Morris Abraham Cohen was born on August 3, 1887 in a Polish shtetl. While an infant, his family fled Poland to escape the pogroms rampaging through Eastern Europe and settled in the East End of London, England into a life of piety and poverty.

For Morris the pall of poverty was far greater than the path of piety, so at the age of 12 he headed for the streets of London to improve his lot. First, he became a prizefighter, boxing under the names, “Fat Moishe” and “Cockney Cohen,” then a shill for a petty thief, “Harry the Gonif” and finally a pickpocket, sort of a Yiddish Artful Dodger.

In 1900, Morris Cohen was arrested for lifting a man’s wallet and sentenced to 5 years rehabilitation in a Jewish reform school. Upon Morris’s release at the age of 18, his parents who were not keen to have Morris return, arranged for him to work on a farm near Wapella, a town in what would become the Province of Saskatchewan. And so Morris crossed the ocean, took a CPR train to Western Canada where he labored as a farmhand but also learned in the Wild West, the skills of dice control, playing card manipulation and pistol marksmanship.

After a year, Morris ran away with the circus, becoming a sideshow barker, enticing rubes to part with their money to watch a show not worth seeing. Ending up in Winnipeg, he began to sell knock-offs before that word was even invented – fake gold rings and jeweled watches. While in Winnipeg, Morris spent 6 months in “cheder” (a Yiddish word colloquially meaning, “jail”) on a prostitution related charge.

At the age of 22, Morris moved to Saskatoon where he often frequented illegal Chinese gambling dens particularly one run by Mah Sam in the back of his café. In 1910, a fateful encounter would later change Morris Cohen’s life forever. Upon entering Mah Sam’s café for food and gambling, Morris stumbled into an armed robbery. He cold-cocked the robber and threw him out. At that time, a white man coming to the aid of a Chinese was almost unheard of. Morris and Mah Sam soon became close friends. Mah Sam had a secret. Not only was he a café owner and a gambler but also a revolutionary, a supporter and fundraiser for Sun Yat-sen, the Chinese republican leader who was attempting to seize power in China and would later become the much-revered father of modern China. Mah Sam introduced Morris Cohen to this world.

While in Saskatoon, Cohen went back to “cheder,” one year in the Prince Albert Penitentiary for pickpocketing. Upon his release in 1911, he moved to Edmonton where he became a successful real estate salesman in the rapidly expanding city. Alas, success came to an end in 1916 with the collapse of Edmonton’s economy and the closure of his real estate office. By that time, the Great War had broken out and Cohen with a sense of patriotism and limited other prospects enlisted in the Canadian Army. Cohen’s army service was distinguished by contracting gonorrhea in England and 9 months of front line service in France. Cohen returned to Canada in February 1919 and was honorably discharged in Edmonton. He was awarded the British War and Victory Medals.

Cohen returned to selling real estate and to gambling. However, Chinese nationalism, introduced to him by Mah Sam, obsessed him. He soon immersed himself in the Chinese community, traveling throughout Western Canada, attending their lodge meetings, advocating on their behalf and fund raising for their cause. He and his work came to the attention of Sun Yat-sen, who by 1922, had established a self-proclaimed military government in Southern China and was its president, though the North was still in the hands of local warlords and civil war was flaring. Approached by Sun Yat-sen to assist in closing a railroad construction contract for China with a Canadian firm, Cohen sailed for China on November 23, 1922 with eight guns secreted in his luggage. With Cohen’s help, the contract was successfully concluded.

Jewish Chopsticks

Moshe Avraham (Morris) Cohen, aka Mah Kun, was the right man in the right place when it came to the establishment of the Jewish state. The only foreign national hero from China, his lobbying at the United Nations’ debate on the Resolution on the Partition of Palestine influenced the delegation from the Republic of China to view the establishment of a Jewish state favorably.

A Stormy Start

One of eight siblings, Morris Cohen was born in 1887 into a poor Orthodox family in Radzanów, northwest of Warsaw. Soon after his birth, the family immigrated to London’s East End. Already sturdy, at just eight years old, Cohen was signed up by a boxing professional. But fearful of his father, Fat Moisha, or Cockney Cohen as he was known, never went into the ring on Shabbos. When he was thirteen, he was arrested for pickpocketing and sent to the Hayes Industrial School, where he should have been reformed into a respectable citizen. Three years later, Cohen’s parents shipped their son to Western Canada to work on a friend’s farm and mend his ways. A year later, however, he was traveling through the provinces making a living as a carnival talker and gambler.

Over time, perhaps bonding with strangers in a strange land, Cohen befriended some of the Chinese workers who had come to lay the Canadian Pacific Railways. Their camaraderie ran so deep that when Cohen saw a Chinese restaurant owner being robbed, he knocked out the thief. In an era when few white men came to the aid of the Chinese, Cohen’s act of rescue catapulted him into Chinese society. His sense of belonging was further solidified when Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen visited Canada in 1908. To help Sun’s cause, Cohen began to recruit members of the Chinese community and train them in drill and musketry.

China Calls

Cohen, who had become a successful real estate broker in Alberta, spent World War I fighting with the Canadian Railway Troops in Europe where part of his job involved supervising Chinese laborers. But after the war, in 1922, with the real estate boom over, he heard China calling

Sun Yat-sen, who had been elected the provisional President of the Republic of China in 1911, was leading China into modernity. However, he was continually challenged by various warlords and, in 1917, China was still without a proper central government. Attempting to reunify the country, Sun joined forces with communist Chinese in the south to challenge the Beiyang government in the north.

Cohen, who arrived in China in 1922, became commander of Sun’s 250-man bodyguard detail. As military adviser and arms dealer, he accompanied the Chinese leader to conferences and into war zones. After one fight, where Cohen was nicked by a bullet, he began toting a gun on his shoulder in addition to the hip weapon he already carried, earning himself the name Two-Gun Cohen. Although he never led soldiers to war, in recognition of his efforts for China, Cohen was awarded the rank of general. Sun, who became known as the founding father of the Republic of China, died in 1925. Cohen was the only foreigner in the funeral procession. He remained in China and went on to work for a series of southern Chinese leaders.

When the Japanese invaded China in 1937, Cohen joined the fight, rounding up weapons for the Chinese. Cohen was in Hong Kong when the Japanese attacked in December 1941. Prompted by his loyalty to his former employer, Sun managed to place Soong Ching-ling, Sun’s wife, and her sister onto one of the last planes out of the British colony. But he stayed behind to fight. When Hong Kong fell later that month, he was imprisoned in the Stanley Prison Camp. He languished there until 1943, when he managed to secure his own release in a rare prisoner exchange by posing as a Canadian businessman. Back in Montreal, just as his father would have wanted, Cohen married a Jewish woman, Judith Clark, and tried to settle down to family life.

Jewish Activist

Jewish Activist

Historically, Chinese-Jewish relations were positive. When the Shanghai Zionist Association lobbied for China’s support for Britain’s Balfour Declaration, Sun Yat-sen expressed sympathy for the Zionist movement, calling it, in 1920, “one of the greatest movements of the present time.”

Zionism and China next met in June 1945, at the San Francisco founding of the United Nations where the debate on the UN Resolution on the Partition of Palestine was taking place. The United States, the USSR, Britain, the Republic of China and France were the five deciding powers. The Arab UN members were putting the pressure on, arguing that Palestine should revert to UN trusteeship rather than be transformed into a Jewish Homeland. To bolster their position, the Arab states stressed to China the need for Asian solidarity, a plea that could have swayed the Republic to oppose Zionism.

Dr. Israel Goldstein, who headed the conservative Congregation B’nai Jeshurun on New York’s Upper West Side and was president of the Zionist Organization of America, was on hand with a delegation to ensure that the Jewish rights in Palestine would not be jeopardized. While communication lines with other UN delegations were in place, reaching China proved to be impossible. Then Dr. Goldstein remembered Morris Cohen, aka Two-Gun Cohen, aka Mah Kun. He contacted Cohen and urged him to fly to San Francisco and provide an introduction to the inaccessible head of the Chinese delegation, General Tung Pi-Wu.

Upon meeting the Zionist delegation, General Wu, a recent convert to Christianity, said, “You are my spiritual brothers. There will be no true peace unless justice is done to the Jewish people.”* Cohen helped arrange additional meetings with the more reticent Chinese delegates to press the Zionist cause. When Jewish activists met with Chinese delegate and ambassador to Britain, V. K. Wellington Koo, Koo told them “the Chinese people, too, know the pain of persecution and discrimination based on race and nationality.” By convincing the Chinese delegation to abstain from voting, instead of opposing the partition, the activists helped to ensure that Palestine remained a mandated territory and did not revert to a trusteeship. The way to the establishment of a Jewish state had been eased.

Cohen eventually settled with his widowed sister, Leah Cooper, in Salford, England. He died in 1970 and was buried in Blakeley Jewish Cemetery in Manchester. His trilingual headstone, engraved in English, Hebrew and Chinese pays tribute to a man who stood up for the persecuted and who thus merited to be the right man in the right place.

Two Gun was the Bull in the China Shop that Fanny knew she needed to support the plan for Israeli Statehood

As the war ended, the United Nations, newly formed, was to become seized with the Palestine problem. Zionist representatives were actively lobbying U.N. members but had no entree to the Chinese delegation. Morris Cohen was approached for help. Cohen who himself was an ardent Zionist, often speaking even when living in China of the need for a Jewish homeland, readily agreed. The U.N. was meeting in San Francisco and Cohen went there to introduce the Chinese delegation, all of whom he knew personally, to the Jewish representatives. These lobbying efforts, all orchestrated by Cohen, were successful in laying the Jewish cause before the Chinese who likely had never before heard of Zionism. Later when the “partition” vote was to be presented to the U.N. and it was believed that China was prepared to vote against the establishment of the Jewish State, Cohen met with the Chinese Ambassador to Canada who was part of the Chinese delegation to the U.N. Rather than voting against partition, China, conceivably because of that meeting, abstained.