Jewish-Chinese Connection During WWII: How a Chinese Diplomat Saved Thousands of Jews

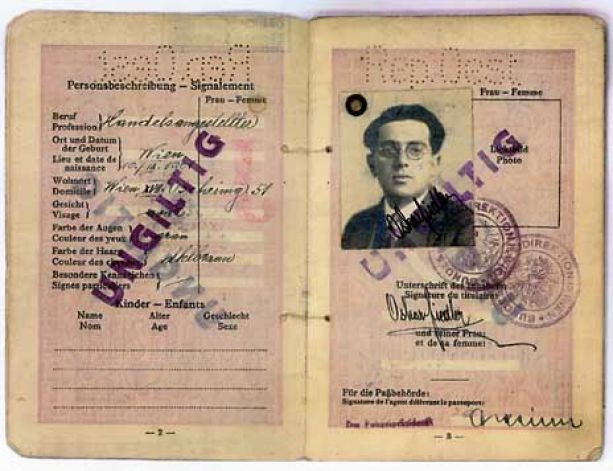

Tens of thousands of Jews living in Austria wanted to leave their country after Germany annexed Austria in March 1938 and started persecuting the Jews. The persecution of Jews in Austria (and in Europe in general) came to a peak on November 9-10, 1938 with a series of attacks on Jews known as “Kristallnacht” (also known as the Night of Broken Glass). During Kristallnacht, Jewish homes, shops, towns and villages were ransacked, as SA stormtroopers and civilians destroyed buildings with sledgehammers, leaving the streets covered in pieces of smashed windows—the origin of the name “Night of Broken Glass.” In Vienna alone, 95 synagogues or houses of prayer were destroyed. However, in order for Jews to leave Austria, they needed to have a visa from a foreign country. This was not easy, especially after the July 6-13, 1938 Evian Conference. This was a conference initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss the issue of increasing numbers of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution, but the result of the conference was that 31 countries (out of a total of 32, with the Dominican Republic as the only exception) refused to increase or even allow Jewish immigrants due to their fear of Nazi Germany. Dr. Ho Feng-Shan, the young Chinese consul-general in Vienna from May 1938 to May 1940, risked his life and career and acting against the orders of his superior, Chen Jie, the Chinese ambassador to Germany, issued visa to any Jew who requested one.

Tens of thousands of Jews living in Austria wanted to leave their country after Germany annexed Austria in March 1938 and started persecuting the Jews. The persecution of Jews in Austria (and in Europe in general) came to a peak on November 9-10, 1938 with a series of attacks on Jews known as “Kristallnacht” (also known as the Night of Broken Glass). During Kristallnacht, Jewish homes, shops, towns and villages were ransacked, as SA stormtroopers and civilians destroyed buildings with sledgehammers, leaving the streets covered in pieces of smashed windows—the origin of the name “Night of Broken Glass.” In Vienna alone, 95 synagogues or houses of prayer were destroyed. However, in order for Jews to leave Austria, they needed to have a visa from a foreign country. This was not easy, especially after the July 6-13, 1938 Evian Conference. This was a conference initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss the issue of increasing numbers of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution, but the result of the conference was that 31 countries (out of a total of 32, with the Dominican Republic as the only exception) refused to increase or even allow Jewish immigrants due to their fear of Nazi Germany. Dr. Ho Feng-Shan, the young Chinese consul-general in Vienna from May 1938 to May 1940, risked his life and career and acting against the orders of his superior, Chen Jie, the Chinese ambassador to Germany, issued visa to any Jew who requested one.

Before he became the Chinese consul-general in Vienna starting in May 1938, Ho was already working at the Chinese legation office [1] in Vienna in 1937. So he observed first hand the persecution of Jews in Vienna after Germany annexed Austria in March 1938. The Jews tried desperately to get a visa from the many foreign missions in Vienna. But almost all refused, because those governments didn’t want to offend the Nazi government. In his memoir, 40 Years of my Diplomatic Life, published in 1990, he wrote “Since the annexation of Austria by Germany, the persecution of the Jews by Hitler’s ‘devils’ became increasingly fierce. The fate of Austrian Jews was tragic, persecution a daily occurrence. There were American religious and charitable organizations which were urgently trying to save the Jews. I secretly kept in close contact with these organizations. I spared no effort in using any means possible. Innumerable Jews were thus saved.” Ho decided to give a visa to any Jew who applied for one. When this became widely known, many people would queue up outside the consulate.

When his boss, the Chinese ambassador to Berlin, Chen Jie, learned of this, he telephoned Ho and ordered him to stop so as not to damage the relation between China and Nazi Germany. Keep in mind that the then Chinese President, Chiang Kai-shek, had a close relationship with the German government. He used German military advisers and weapons, and had also sent his younger son, Chiang Wei-guo, to Germany to be trained by the Nazis. However, Ho did not follow the order and continued to issue visas to any Jew who applied. The ambassador even sent an officer to Vienna to investigate whether Ho was profiting from the visas. But no evidence of bribery was found.

In early 1939, the Nazis confiscated Ho’s consulate on the pretense that it belonged to a Jew. Ho asked his government for relocation funds, but was refused, the reason being that China did not have the funds because it was at war with Japan. Ho rented smaller facilities at his own expense, and continued to issue visas to Austrian Jews until he left Vienna in May 1940. On November 10, 1939, he went to the home of one Jewish family to see them off after he had issued them visas. The Gestapo had arrested the father. Ho confronted the Nazi officers, who pulled a gun on him, resulting in a tense face-off. Finally the Gestapo backed down because they realized that Ho was a diplomat who issued valid visas. The family was then allowed to leave for Shanghai.

It is not clear how many visas Ho had issued by the time he left Vienna in May 1940. We do know that by October 1938, or five months after he became the Chinese consul-general in Vienna, he had already issued 1,900 visas. Then came Kristallnacht in early November 1938 and persecution of Jews intensified, so more Jews wanted to emigrate. By September 1939 when war broke out in Europe, almost 70% of the approximately 185,000 Jews registered in Austria (about 90% lived in Vienna) had already emigrated, but of course to many countries, and not just to China. We also know that by that time (September 1939), more than 18,000 European (not just Austrian) Jewish refugees had arrived in Shanghai. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the number of visas issued by Ho to Austrian Jews from May 1938 to May 1940 was easily over 10,000. This does not necessarily mean that all these Austrian Jews settled in Shanghai, because they could use the Chinese visa to leave Austria and then go to other countries to settle.

It is not clear how many visas Ho had issued by the time he left Vienna in May 1940. We do know that by October 1938, or five months after he became the Chinese consul-general in Vienna, he had already issued 1,900 visas. Then came Kristallnacht in early November 1938 and persecution of Jews intensified, so more Jews wanted to emigrate. By September 1939 when war broke out in Europe, almost 70% of the approximately 185,000 Jews registered in Austria (about 90% lived in Vienna) had already emigrated, but of course to many countries, and not just to China. We also know that by that time (September 1939), more than 18,000 European (not just Austrian) Jewish refugees had arrived in Shanghai. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the number of visas issued by Ho to Austrian Jews from May 1938 to May 1940 was easily over 10,000. This does not necessarily mean that all these Austrian Jews settled in Shanghai, because they could use the Chinese visa to leave Austria and then go to other countries to settle.

After Japan conquered Shanghai in November 1937, Shanghai was occupied by the army of Japan, and Shanghai allowed foreigners to enter Shanghai without visa or passport. So Austrian Jews did not require the Chinese visa to enter Shanghai, but they needed a visa to leave Austria. At that time, there were two main Jewish communities in Shanghai: The more wealthy Baghdadi Jewish community (coming mostly from Iraq) and the less wealthy Russian Jewish community. In February 1943, Japan issued the “Proclamation Concerning Restriction of Residence and Business of Stateless Refugees” that required Stateless Refugees to relocate to the “Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees,” also known as the “Shanghai ghetto.” Stateless Refugees are those refugees who “arrived in Shanghai since 1937 from Germany (including former Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, former Poland, Latvia, and Estonia, etc) and have no nationality at present.” The Shanghai ghetto was an area of approximately one square mile in the Hongkou District of Japanese-occupied Shanghai. About 20,000 Jewish refugees were relocated there, together with the Chinese who were already living there. The Ohel Moishe Synagogue, located in the Hongkou District, was established in 1907 to serve the Russian Jewish community. It was renovated and re-opened to the public in 2008 as the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

After he left Vienna in May 1940, Ho transferred to New York and did political analysis, and then he returned to Chongqing, China’s wartime capital, to help in the war effort against Japan. In 1947, he was appointed as the Chinese ambassador to Egypt and several other middle Eastern countries. After serving in the Middle East, he then served as the (Nationalist) Chinese’s ambassador to Mexico, Bolivia, and Colombia. He retired in 1973. Although he served as a diplomat for his country for almost 40 years, he was denied a pension by the Chinese Nationalists with the reason being that he could not account for about US$300 of embassy expenses. His daughter Ho Manli believed that the snub with the pension was not a retaliation against what he did in Vienna, but because later on he offended Chiang Kai-shek’s oldest son, Chiang Ching-kuo. After retirement, he lived in California, until he died on September 28, 1997, at age 96. Taipei was not represented at his funeral, but Beijing’s consulate in San Francisco sent a wreath.

Ho was a humble man. His daughter said “He was generous in nature. To help other people was very natural. From a humanitarian point of view, it was what you should do. There was nothing much to say.” Perhaps this attitude originated from his deep religious beliefs, which were instilled by Norwegian Lutherans who raised him after his father died and left his family destitute. Even though his 1990 memoir was 290 pages long, it contained only 10 pages on his tenure in Vienna. As a matter of fact, his heroic deeds in Vienna almost went unrecognized. It was after his death in 1997 that his daughter Ho Manli posted an obituary in a newspaper, with one line about her father’s work in Vienna. This was read by Dr. Eric Saul, an American professor of Jewish history and a Holocaust historian, who then embarked on the painstaking work of collecting evidence from those (and their descendants) who had received visas from Ho. Only after that, did Ho, who may have been responsible for saving the lives of more European Jews than any other single individual, received the recognition that he so deserved. In 2001 he was awarded the title “Righteous Among the Nations,” which is Israel’s highest civil award, bestowed by Jerusalem on non-Jews who helped Jews at the risk of their own lives. The awardees are remembered in the Yad Vashem, the Holocaust History Museum in Jerusalem. Ho is now also known as “The Schindler of China.”

Below are four photos I took in 2009 when I accompanied the “New Jersey Alliance for Learning and Preserving the History of WWII in Asia” (NJ-ALPHA) on the China Study Tour organized for American high school/college teachers/educators. The photos were taken at the “Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum” which used to be the Ohel Moishe Synagogue in the Hongkou District. This synagogue was established in 1907 to serve the Russian Jewish community that flourished in Shanghai. It was recently renovated and re-opened to the public in 2008 as the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum. You can see a bigger-size photo by clicking on the thumbnail photo.